As we explore the history of cocktails and their origins, we’re beginning to notice a recurring theme: there seem to be half a dozen competing theories about the invention of nearly every recipe. The Old-Fashioned is claimed by a who’s-who of Gilded Age aristocrats, there are at least two Counts Negroni complicating matters in Italy, and the Mint Julep‘s ancestry is so ancient that it’s impossible to tell when it stopped being medicine and started being a drink for Southern gentlemen. Perhaps the most classic of all cocktails, the Martini, is no exception.

If you poke around online and in the cocktail literature, you’ll probably happen upon at least a few different versions of the history of the Martini. In his seminal book Imbibe!, David Wondrich outlines the frontrunners in great detail—drawing from his research and a number of other sources, we’ve compiled a summary of our three favorites. We have our hunches about which seems most likely, but you’ll have to make up your own mind.

Martinez

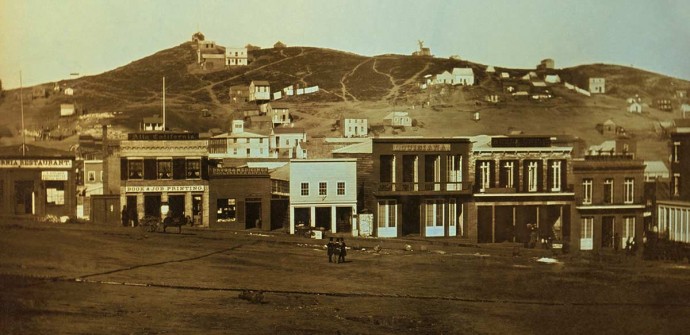

The first two stories come out of the San Francisco Bay Area in the latter half of the 1800s, shortly after the height of the Gold Rush. San Francisco had blossomed from a mere 200 residents in 1846 to nearly 36,000 in the 1850s, and was ripe for any number of cultural and culinary inventions. The staunchest claimants to the Martini Cocktail, though, hail from across the Bay in the city of Martinez.

If the legend (and the city itself) is to be believed, a bartender by the name of Julio Richelieu first improvised the drink for a gold miner in the mid-1870s. The recipe consisted of gin, sweet (Italian) vermouth, orange bitters, maraschino liqueur, and a lemon twist, and it became a fashionable order when Richelieu later set up shop in San Francisco. The details of this story differ from telling to telling—some say the miner had struck it rich and requested champagne to celebrate, but the saloon was fresh out and Richelieu tried to make him something equally fancy. Other versions have the prospector overpaying for a bottle of whiskey with a gold nugget, and instead of giving change the bartender mixed him a special drink.

It’s a reasonable-sounding tale, even if the details are fuzzy, and it would be fairly convincing if not for a few inconsistencies. For one, this account didn’t appear until 1950. Though the city of Martinez defends its claim aggressively, it doesn’t seem that anyone in town cared one way or another about Martinis until after the story began to circulate. And perhaps more damning is the fact that Julio Richelieu, the supposed creator of the cocktail, doesn’t appear in any California census records or really seem to have existed at all. These, plus a number of other small disparities, would seem to indicate that Martinez’s version of events is little more than a case of overzealous hometown pride (and a convenient new hook for the tourism department).

San Francisco

This next one, while close to our hearts as San Franciscans, looks a bit unlikely as well. First laid out in a Beefeater gin ad in the 1960s, the story goes that legendary bartender Jerry “The Professor” Thomas came up with the recipe in the 1860s in San Francisco. A patron was on his way to the aforementioned town of Martinez, so he whipped him up something special as a sendoff. The Martinez recipe was later published in the 1887 edition of his Bar-Tenders Guide.

But as much as we love our patron saint of mixology, the Jerry Thomas theory doesn’t seem to hold water. Perhaps most importantly, he never once claimed to have invented the drink. It was absent from the first edition of his Guide, and as David Wondrich notes, “nor did Thomas himself mention it to any of the many reporters who interviewed him or wrote about him, and he was not the type to hide his light under a bushel. If he had invented it, it is almost inconceivable that nobody at the time would have known it or mentioned it.” Sorry, Jerry. Looks like you’ll just have to settle for being the most influential barman who ever lived.

New York

This last version, much to our Californian chagrin, revolves around New York City. It attributes the Martini to Judge Randolph B. Martine, a prominent member of the Manhattan Club, which at the time was one of the city’s most revered drinking establishments. This is supported by dozens of early recipes that refer to a “Martine Cocktail,” as well as the International Association of Bartenders’ own records from 1893. The first printed record associating Judge Martine with the cocktail didn’t appear until 1904, though—nine years after his death.

Despite the posthumous ascription, this looks to be one of the more plausible theories. The name “Martini” obviously won out over time, but this is likely due to the fact that, in New York anyway, the drink would typically have been made with Martini brand vermouth. The similarity of the monikers probably led to some confusion, and eventually people figured the drink was named after one of its ingredients. Chances are we’ll never know for sure, but Judge Martine looks like a strong candidate for the father of the Martini.

As fascinating and controversial as the Martini’s origins may be, what’s even more compelling is how drastically the recipe has changed over the years. We’ll cover the evolution of the drink in another piece—it’s a recipe that’s proven amazingly flexible, and as we noted in our previous Martini article, one that inspires near-religious fanaticism. Check back soon to see what all the fuss is about.