Passing through your local Irish whiskey aisle, you may see bottles labeled “Single Pot Still.” It would follow that said whiskey was simply distilled in a singular pot still—right?

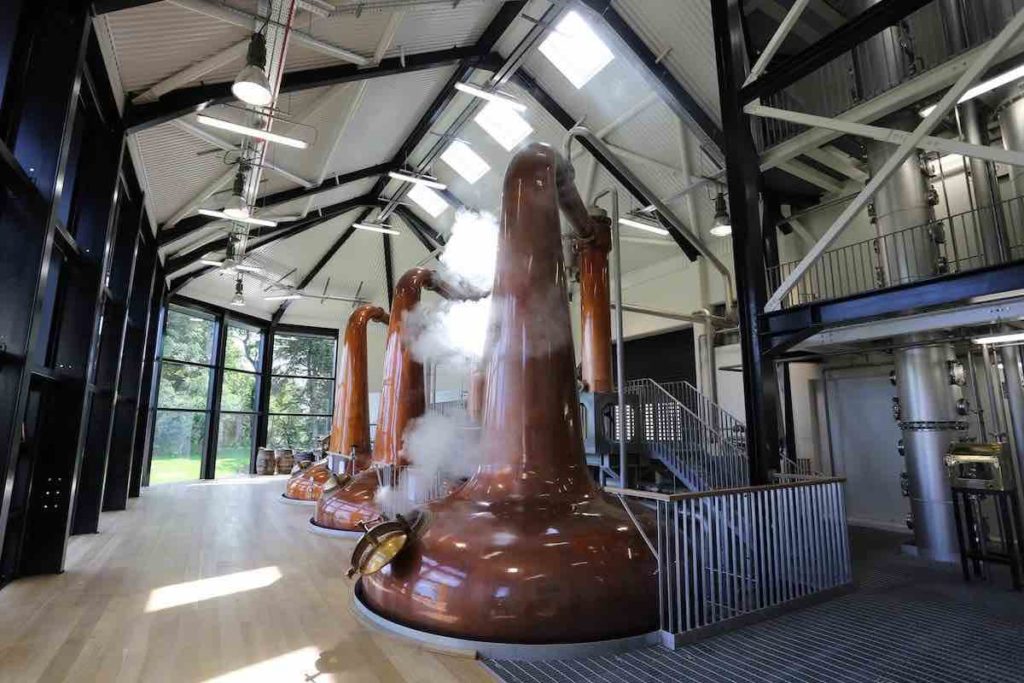

Well, wrong, but we don’t blame you. Irish single pot still is in fact a separate, legally defined category of whiskey whose differentiating factor has more to do with mash bill than still. This is rather confusing, so to break down its history and definition we’ve enlisted the aid of Woody Kane, who works as an ambassador and visitor center manager for Ireland’s Royal Oak Distillery.

Kane has good reason to be familiar with single pot still, as Royal Oak produces the recently released The Busker label, whose lineup includes a single pot still expression (as well as a single malt, single grain, and a blend that combines all three).

As is the case with single malts, the “single” here means it was produced at a single distillery (if not, it would simply be a “pot still whiskey”). But rather than distilling from 100% malted barley, pot stills are made from a mix of both malted and unmalted barley, with a small portion of the mash bill left aside for other grains.

An Unusual Tax Loophole

This arrangement arose in the 17th century, when the occupying English began to levy taxes on malted barley. Irish distillers reacted in much the same way as we would today—by finding a loophole. By distilling from a mix of malted and unmalted barley, Ireland’s distillers could continue making whiskey in mostly the same way they’d grown accustomed to while saving a bit of money.

But once the final product was poured, people realized they had something else entirely. “We introduced this unmalted barley in with the malted barley, and once we began that you’re looking at a completely different animal,” Kane says.

A Distinctive Character

Obviously, Ireland’s distilleries have been free of English taxation for some time, but they continue to produce single pot still whiskey. That’s thanks to the distinctive qualities the malted/unmalted blend contributes to the whiskey, which Kane defines as a nose typified by black peppercorn, a light, creamy texture, and a greater spice factor without necessarily having a higher proof.

“A lot of people would find it tastes stronger, and mistake it for having a higher alcohol content,” he says. “You’ll have a low alcohol volume, and people would taste it and think it’s strong, but it’s not.”

Kane says that Ireland’s single pot still whiskeys became a tremendously popular export but suffered with the rest of the nation’s industry following the closely timed calamities of World War One, American prohibition, and Ireland’s trade wars with the United Kingdom following its independence. But as a resurgent Irish whiskey industry continues to grow in popularity abroad, Kane sees single pot stills as having an important place in the category’s comeback.

“Pot still is that golden gem,” he says. “If you want to drink a whiskey from Ireland, pot still is an important thing to take on because it gives you what we’ve had from the past.”

Irish Single Pot Still Whiskey Basics

To be considered an Irish single pot still whiskey, the whiskey must be:

- Made in Ireland at a single distillery (Irish pot still whiskey that is not labeled single pot still can be produced by multiple distilleries).

- Composed of a mash bill that contains at least 30% malted barley, at least 30% unmalted barley, and up to 5% of other grains including rye or oats.

- Distilled in pot stills.

- Aged in wooden casks for a minimum of three years, per the legal requirements of Irish whiskey.

How to Drink Irish Pot Still Whiskey

The oily texture and rich spice of a single pot still whiskey makes it an excellent candidate for neat sipping, but it has its charms in cocktails, too. Thanks to its more robust body and spice contingent, you can expect a pot still whiskey to stand up to other ingredients and make a bang-up Tipperary, for one example.