With the Margarita, we venture back into the all-too-familiar territory of cocktails with mysterious origins. Unlike the history of the Daiquiri or the history of the Moscow Mule, it’s not entirely clear who came up with the world’s most popular tequila cocktail.

Like the Martini before it, there are several competing stories, none of which are quite air-tight enough to convince us one way or another. Of course, one or two of them are hilariously unlikely, so for now it seems the best we can do is agree on who definitely didn’t invent it.

But without further ado, let’s dive into the history of the Margarita.

The Tequila Daisy

As with any great cocktail (save for the first cocktail ever created, of course), the Margarita’s story starts with its ancestors.

By the late 19th century, a whole class of cocktails known as Daisies had come to be quite popular in the States. The Brandy Daisy was a standout favorite, and its simple recipe—brandy, triple sec (simply referred to as curaçao back in the day), and lemon juice—is thought by some cocktail historians to be the predecessor of the Margarita.

But the similarity of the recipes alone isn’t enough to claim ancestry. If that were the case, we could just as easily claim that anything with citrus and sugar in it was descended from the Daiquiri.

The important connection between these two drinks, though, is in the name: margarita is actually the Spanish word for daisy. So how did a classic brandy cocktail come to be made with tequila, a distinctly new-world spirit?

The Picador

Well, before we get to that, there’s something of a missing link we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention. The Picador, as published in the Cafe Royal Cocktail Book in London, first appeared in print in 1937. The recipe called for a 2:1:1 ratio of tequila, Cointreau, and lime juice, which (for those of you keeping score at home) is more or less the same as the recipe for the classic Margarita.

While we doubt this was the first instance of the proto-Margarita, it’s one of the more concrete ancestors out there. Most of the others are a bit vague or otherwise shrouded in controversy—the Picador, on the other hand, is firmly recorded in print.

Prohibition and the War

We know that the Margarita resembles the Daisy in both recipe and name, and we know that something very similar to a Margarita had been invented by the late ’30s. The mystery, then, concerns who gets the credit for making it first.

As always, the answer is likely tied up in the consequences of Prohibition.

When the 18th Amendment went into effect in 1920, organized criminals rejoiced. Americans would soon be willing to pay exorbitant markups on alcohol smuggled in from Canada, Europe, and Mexico, and they stood to profit (hence, you know, Al Capone).

These smuggling operations marked the introduction of new spirits to the US, one of which was tequila. Formerly reserved for rough-riding westerners along the border, it gradually made its way north to fill the void that was created when domestic distilleries shut their doors.

The Daisy was still a fairly popular drink heading into the ’20s, and somewhere along the line, an enterprising (or clumsy, depending on the story) bartender swapped out the brandy for some newly-arrived tequila. Apparently, the invention was a hit.

As Prohibition wore on, these “Tequila Daisies” began popping up on various speakeasy menus throughout the country. They weren’t as widely available as concoctions made with Canadian whisky or other, more familiar spirits, but they certainly made an impression. Most likely, a Spanish-speaking bartender did some translation, and the Margarita was born.

After the 21st Amendment repealed Prohibition in the States, it wasn’t long before the outbreak of WWII in Europe caused yet another shortage. A paucity of imported brandies and other traditional spirits set the stage for a second tequila boom, and by the mid-’40s it was truly ensconced as part of American drinking culture.

Esquire and the Socialite

Of course, while likely, “some Prohibition-era bartender, either in Mexico or an American speakeasy” is never going to be a satisfactory claimant to the invention of the Margarita. As a result, it’s not surprising that other “inventors” came out of the woodwork once the drink became popular.

The most famous of these pretenders was a socialite from Dallas, Texas by the name of Margarita Sames. In a 1953 issue of Esquire magazine, she was credited with inventing the drink at a Christmas party she threw at her Acapulco vacation home in 1948. Her guests were so enamored with their hostess’ recipe that they decided to name it after her.

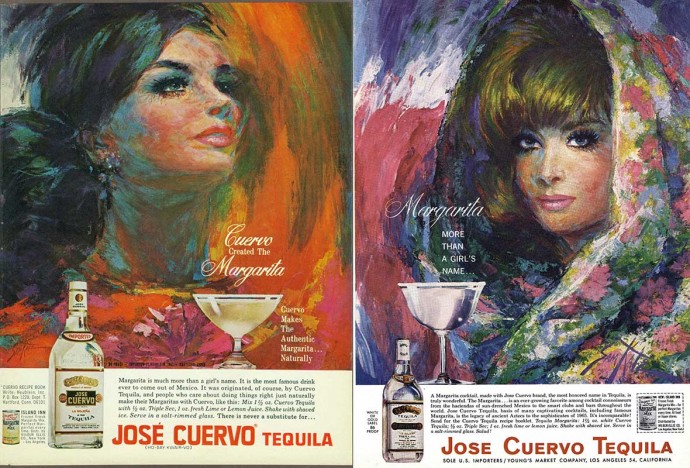

Those guests, however, were apparently oblivious to the fact that the Margarita had been a well-known cocktail in the United States for at least three years. In fact, a 1945 ad campaign for Jose Cuervo featured the tagline “Margarita: it’s more than a girl’s name.”

So, as anything other than a passing curiosity (and easy ammunition for poking fun at Esquire), the Margarita Sames story doesn’t add up to much.

Blame 7-Eleven

Like many of its beachy cousins, the Margarita eventually ended up with a frozen variant. Originally made to order with either hand-crushed ice or in a blender, by the 1970s it was clear that high-volume bars needed a better way to prepare the drinks en masse.

Enter Mariano Martinez, a restaurateur from Margarita Sames’ hometown of Dallas (as far as we can tell, the connection is coincidental). As demand for Frozen Margaritas skyrocketed, he went on a mission to solve the problem of large-scale production once and for all.

Apparently, that mission only took him about a block and a half down the street to his local 7-Eleven, where he happened upon a Slurpee machine. Inspired by their design, he bought himself a soft-serve ice cream machine and modified it to create large batches of blended Margaritas.

Problem solved, legacy among spring breakers everywhere cemented.

The Drink That Never Dies

Ever since the explosion in popularity that followed, the Margarita has never really gone out of style. Perhaps that’s because it’s only called for on specific occasions, like resort vacations in Mexico or trips to your local Mexican restaurant—we don’t have enough exposure to get tired of it.

More likely, though, its ubiquity is well earned. There’s a reason the Daisy was a favorite at the turn of the 20th century, and it’s the same reason its descendant was remained one well through the turn of the 21st: booze, lime juice, and triple sec were simply meant for each other.

What do you call a rum daisy with Orgeat? A Mai Tai.