This post is part of our Rum Hub.

Relatively speaking, the history of the Daiquiri isn’t mired in all that much hearsay and ambiguity compared to its fellow classic cocktails. That’s probably because it took all of about fifteen minutes to go from drunken, late-night experiment to wildly fashionable among the movers and shakers inside the Beltway (it was more like nine or ten years if you want to be technical), so there wasn’t a whole lot of time for the origin of the recipe to get lost.

As with all of these histories, though, we can’t be absolutely certain about the prevailing narrative. People have been mixing all kinds of crap into their booze for millennia, and as long as the right ingredients were available, it seems likely that similar or even identical recipes have been invented by dozens of people who simply never met (or failed to market their creation properly, the cardinal sin of bartending).

When it comes to the Daiquiri, though, there seems to be a pretty clear chain of events that connects its invention to its explosion in popularity. And while its origins might not be particularly mysterious, they’re still absolutely fascinating.

The Daiquiri and the Spanish-American War

Don’t worry, we’re not going to give a lecture on the intricacies of the Spanish-American War (although the conflict seems to have had an inordinately large influence on cocktails—Remember the Maine, anyone?), but it deserves some mention here due to its role in setting the stage for the Daiquiri to exist in the first place.

Thanks in part to advocacy by then-Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt (and a combination of the Monroe doctrine and the potentially-accidental sinking of the USS Maine and generally negative attitudes toward Spain in America and… sorry, we said we wouldn’t do that), the United States intervened in the Cuban War of Independence by blockading the island on April 21st, 1898.

Shortly thereafter, Roosevelt and his Rough Riders—an all-volunteer cavalry regiment he had put together after the war began and he resigned his civilian post—landed at Daiquirí beach in southeastern Cuba, forever cementing the name in American folklore. The nearby village became a focal point of the US invasion, and after about three and a half months (as well as several extremely bloody battles), the Americans succeeded in driving the Spanish from the country.

What followed was a bit of shady backpedaling from Congress, which had promised Cuba that American involvement wasn’t an attempt to annex the country. After the end of the war, though, they passed the Platt Amendment, which granted the US massive amounts of control over Cuban affairs without technically violating the terms they had agreed upon beforehand. As a result, American businesses moved in to snatch up the economic resources that had been left behind by the Spanish.

A Late-Night Booze Run

But enough about turn-of-the-century geopolitics, let’s get back to the cocktail. The sudden influx of American investment into Cuban agricultural and mining interests meant that there were a lot of farmers, engineers, and other professionals making their way to the island after the war. One such mining engineer, Jennings S. Cox, found himself somewhat haplessly stumbling into the annals of cocktail history.

The story goes that one night, while entertaining guests at his home near the village of Daiquirí, Cox ran out of gin. Probably in something of a panic (we’re editorializing, but we’ve all been there), he ran out to the village market to scrounge up an alternative. As you’d expect, the only thing he could find was a local rum—likely Bacardi, which had started distilling in Cuba nearly forty years prior. Apparently worried about the sensitive palates of his American guests, Cox decided to mix the stuff with some lemon juice and sugar in a punch bowl, and voila. The Daiquiri was born.

While we don’t doubt that some version of this account actually happened, it’s a bit ridiculous to credit an American expat with the invention of a drink that had probably existed locally for decades, if not centuries. As we mentioned in our history of the Mojito, people had been cutting their rum with citrus juice and sugar ever since it was first introduced to the Caribbean, mostly to take the edge off of what was essentially the bathtub hooch of its time.

There was even a proto-Daiquiri that was popular among Cuban revolutionaries in the 19th century known as the Canchánchara, which consisted of two parts rum to one part lemon juice, and would certainly have been common in the area around Santiago where Cox lived and worked. So, while he might have been completely oblivious to it (and, come on, the guy was drinking gin on a tropical island), the engineer had simply added sugar and ice to a local favorite and renamed it. For whatever reason, though, his was the one that caught on.

Heading North

As far as we know, the next big step in the popularization of the Daiquiri came about ten years after Jennings Cox first mixed one up. Rear Admiral Lucius W. Johnson, a medical officer in the US Navy, apparently happened upon the Daiquiri while in Cuba in 1909. He was so taken with the recipe that, upon returning to the States, he introduced it to his friends behind the bar at the Army and Navy Club in Washington, D.C., and from there it spread like wildfire—albeit a really, painfully slow wildfire.

Information traveled slower back then, and for at least another decade the Daiquiri didn’t make it too far outside of Cuba and the Mid-Atlantic. But its momentum grew over time, and the use of lime juice (instead of Cox’s lemon) became the standard. By the time the roaring, Prohibition-fueled ’20s got underway, its position as a classic seemed all but in the bag.

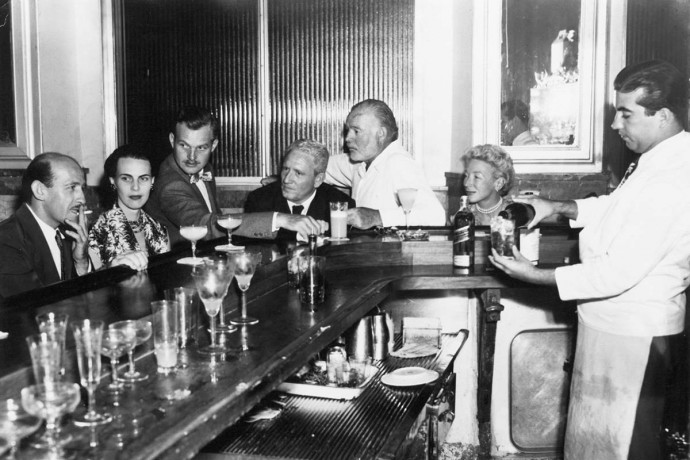

It first appeared in American literature in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise in 1920, and Hemingway sucked them down by the dozen at El Floridita in Havana. The latter seemed thoroughly smitten with the drink, going so far as to come up with a couple variations of his own. The Hemingway Daiquiri leaves out the sugar (as he was diabetic) and goes for a twist on the original citrus with grapefruit juice and maraschino liqueur. He got his nickname “Papa Doble” for his habit of exclusively ordering them as doubles.

The Frozen Daiquiri and World War Two

As the drink grew more and more popular, it underwent some transformations. The famed Cuban bartender Constantino Ribalaigua Vert at El Floridita was responsible for adding crushed ice to his Daiquiris in the 1930s, as advances in refrigeration technology made it easier to come by on the island. The trend caught on, and with the rise of Waring and Vitamix blenders in the latter half of the decade (high drama, we know), Middle America finally got its hands on the Frozen Daiquiri.

Then, of course, came America’s entrance into the Second World War. Wartime rationing made it difficult to come by most distilled spirits, but thanks to President Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor” policy, trade with Latin American nations remained largely unfettered. As a result, rum stepped in to fill the gap and subsequently skyrocketed in popularity—throughout the ’40s, ’50s, and beyond, Tiki bars and tropical drinks were all the rage, with the Frozen Daiquiri (and particularly the Strawberry Daiquiri) squarely among them.

People do certainly love to hate on it, though, and often for good reason. Chucking fruit and booze into a blender isn’t exactly a great way to make a balanced cocktail, and over the decades the drink earned a reputation as a syrupy mess. Most of the time, you’d be better off pouring Bacardi into your gas-station slushie. It doesn’t have to be that way, though, and the original Frozen Daiquiri can be pretty phenomenal when it’s made with some subtlety.

The Daiquiri’s Revival

It wasn’t really until the ’90s that people thought about taking the Daiquiri seriously again. As the cocktail revival got underway in the States, historians and bartenders started working together to dig up original recipes for classics that hadn’t been seen in years. That’s not to say that the Daiquiri was anywhere close to some of the most obscure stuff they were looking for—it’s not like you couldn’t get some semblance of one at any all-inclusive beach resort—but the rise of the craft cocktail bar sparked popular interest in the unfrozen variety for the first time in decades.

As the turn of the 21st century came and went, geeks like us became fascinated with the romantic stories of Hemingway, Roosevelt, and El Floridita. And given that the US only very recently normalized relations with Cuba, for many of us there was the added mystique of drinking something from a (relatively) forbidden country.

Today, it’s trivial in most major cities to find an old-school Daiquiri, and the world is a better place for it. It’s perfectly balanced, beautiful, and ripe for experimentation by seasoned bartenders, so you’re bound to come across some pretty wild variations if you look hard enough. Perhaps most importantly, though, it’s incredibly easy to make at home. So if you’ve ever been hesitant to try your hand at cocktailing, give the classic Daiquiri a shot. On second thought, make it a Doble.

This article is part of a series on the Daiquiri. Don’t miss our pieces on How to Make a Daiquiri and 5 Decadent Daiquiri Variations!

Return to the Rum Hub.

1 Comment