Japan has no shortage of natural wonders. But for cocktail enthusiasts, one stands out in particular: the baseball-sized, hand-carved ice spheres that chill libations in every bar from Sapporo to Osaka.

In April I attended a class at Thirst Boston entitled “Welcome to the Ice Dojo” with the high hopes of carving a sphere of my own. I’d only learned how to use a proper chef’s knife in the previous six months, so this was a tall order. At least my guide would be Gardner Dunn, a veteran NYC bartender and Suntory’s National Brand Ambassador.

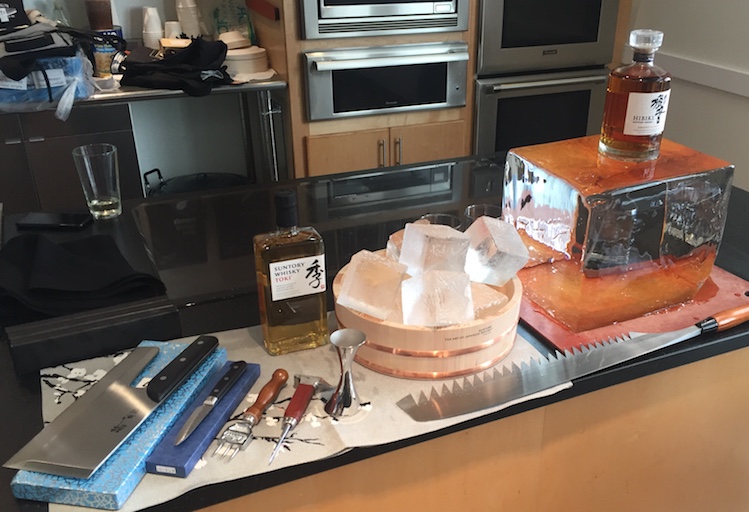

Dunn begins the class by laying out a series of fearsome-looking carving instruments and a titanic block of ice. As he does so, he explains the importance of quality ice to Japanese drinking culture.

“I don’t care if you’re at a dive bar in Golden Gai, or at the Park Hyatt in Tokyo Tower,” says Dunn. “There is no soft ice or fast ice. It’s all hand-delivered.”

He begins to break down the mammoth ice block into smaller cubes using an odd-looking instrument that resembles a butcher’s knife, but with a blade that runs almost parallel to the handle. Dunn explains that this is a soba knife, used for breaking down ice because it cuts on an even plane.

The attendees of the class will be carving the large, square ice blocks into cubes. We will each carve two spheres, using different tools: an ice pick and a knife. We’ve also been given a furoshiki, a type of cloth traditionally used in Japan for gift-wrapping. In this context we’ll be using it to hold the ice while we carve, to slow the melting process.

With my left hand, I cradle the ice block in the furoshiki. Dunn tells us to hold our ice pick like we would a pen, with two fingers on top. He says to think of it as a Rubik’s cube: constantly rotate it, and try to solve each edge as we transform it from square to sphere.

The room is filled with the chirping noise of picks striking ice. Tiny slivers of ice fly in every direction, melting on contact. Within a few minutes of carving my shirt is soaked with cold water. Fresh puddles form at our feet.

Thirst is a cocktail conference. I, and likely most of the attendees, are already one cocktail in. This makes the idea of learning how to use an ice pick a little more intimidating. But Dunn demonstrates the safe way to carve: so long as you are carving away from yourself, there is no danger of striking the palm.

He also cautions never to drop the finished product into your drinking vessel, as it’s likely to shatter the glass. Instead, he recommends we carefully place the sphere inside.

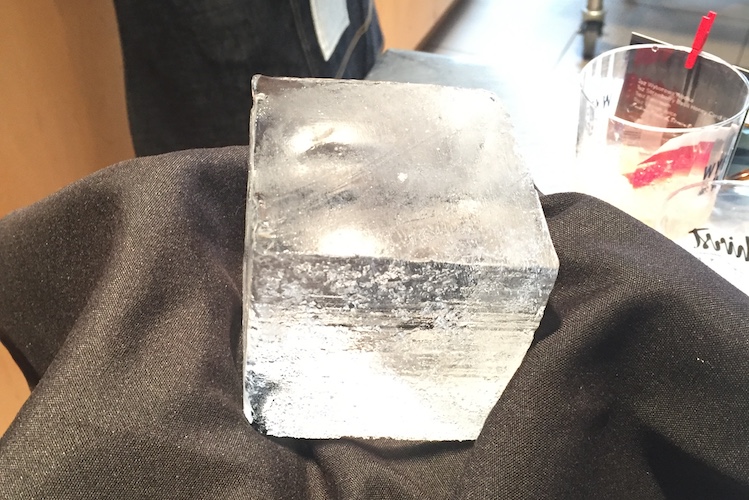

After much whittling, I’ve produced my own little sphere. Ok, sphere might be generous: it’s more like a rough, oval-shaped rock you might find at the beach. But there’s a bottle of Suntory Toki being passed around, and my imperfect ice does an admirable job of chilling the whisky in a glass.

Next we move onto the knife method, fresh ice squares in hand. Dunn instructs us to hold the small, sharp knives within the crease of our hand, at a slight angle. This will give us the leverage needed for proper carving.

Once again, Dunn stresses the importance of rotating the cube as we carve. He asks us to take all four corners into consideration as we do so, and to continue whittling away until the ice resembles a Dungeons and Dragons D12 die.

“The reason I like using the knife is because you get those beautiful corners,” says Dunn. “You’ll notice it’s completely different. It’s a little bit smoother, it’s got some cool lines.”

I wouldn’t describe my own effort as a D12–but at least it’s D12-esque, with some of those interesting lines Dunn was talking about. A bottle of Hibiki Harmony is being passed around, and I prepare to gingerly transfer the ice to my glass. But ice being ice, it slips through my fingers and lands hard in the glass, shattering it on impact. Fortunately my skin is uninjured, but I can’t say the same about my pride. I’ll take it as a learning experience.

The class ends with a question and answer period. I ask Dunn if any bars in the United States are carving ice to Japanese standards. He replies that while the quality of ice is improving stateside, many bars are relying on molds to make spheres rather than carving their own. But he notes that some establishments are practicing the art properly, citing Masa and Angel’s Share in New York, and Green River in Chicago.

Another attendee asks Dunn his thoughts on the ascendance of Japanese whisky. Dunn takes us back to his early days repping Suntory.

“Honestly, I couldn’t give it away eight years ago,” says Dunn. “People would say the Japanese don’t make whisky.”

He recalls how he once used Yamazaki 12 in cocktail competitions–baffling the room. But he notes that bartenders were early adopters of Japanese whisky in the U.S., and helped to bring it into the mainstream.

“The bartenders were the gatekeepers,” Dunn says.

I look around the room. Most of the attendees are bartenders. They’re holding ice picks and carving knives in their hands: many have produced outstanding ice spheres. If they bring what they’ve learned back to their respective bars, another gate may begin to open.

Photos by Eric Twardzik