Cinco de Mayo is an idiosyncratic holiday. Much like St. Patrick’s Day, it has come to be treated as a massive cultural celebration in the United States—complete with excessive amounts of booze—while remaining a relatively low-key affair in its country of origin. But just how did a 19th-century battle go on to become an occasion for Margaritas, sombreros, and other thinly-veiled cultural appropriation? The answer stems from a fascinating historical web of international politics and identity.

Why Do We Celebrate Cinco de Mayo?

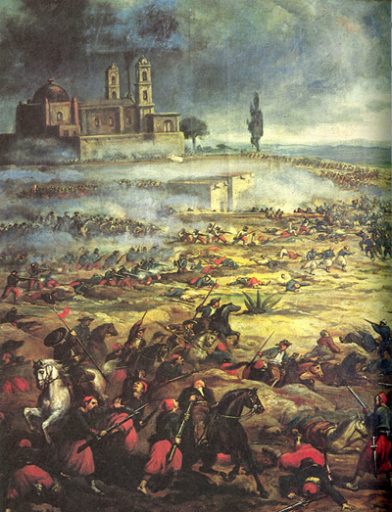

Cinco de Mayo commemorates the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862, one of the first engagements between Mexican and French forces in the Franco-Mexican War. Despite being outnumbered two-to-one, the Mexican Army—under the command of General Ignacio Zaragoza—repelled the French advance into the city of Puebla, and their David-and-Goliath victory has been celebrated ever since.

But the significance of this battle was far greater than a single city.

For some context, by 1862 Mexico was in fairly dire financial straits. Coming off of the Mexican-American War (1846-48) and a subsequent civil war fought over the separation of church and state, known as the Reform War (1858-61), the nation’s coffers were all but empty.

Over the course of those two wars, Mexico had taken on substantial debts to France, Spain, and the United Kingdom, so when President Benito Juárez announced that he was suspending payments to all foreign countries, they were none too happy. On October 31, 1861, the three nations agreed to send troops to Mexico and force them to pay up.

Cinco de Mayo and the American Civil War

Meanwhile, to the north, the United States was thoroughly embroiled in its own civil war. Always looking for opportunities to spread the influence of his empire, Emperor Napoleon III had designs on sending aid from France to the Confederacy—who, at the time, seemed to be making significant gains against the Union. In order to do that (and simultaneously open trade routes to the rest of Latin America), the French would need to conquer all of Mexico.

The Battle of Puebla, May 5, 1862

When the Europeans arrived in Mexico in December of 1861, it became clear to the Spanish and British that France had no intention of sticking to the original terms of the bargain, and they withdrew their forces in April 1862. Having already captured several major cities, the French continued on their warpath with little resistance.

On May 5, though, they suffered their first major defeat at the city of Puebla, suffering more than five times as many casualties as the Mexicans despite attacking with a much larger army. It was the first time the French had lost to a foreign military in nearly 50 years.

The victory was short lived, though, and by mid-1863 the French had succeeded in capturing Puebla and Mexico City, establishing the Second Mexican Empire under Emperor Maximilian I.

That said, the Battle of Puebla gave the Mexican Army a much-needed morale boost, and established General Ignacio Zaragoza as one of the most famous figures in Mexican history. And, perhaps most importantly to the question of Cinco de Mayo’s prominence in American culture, it drastically slowed the French advance and prevented them from offering any aid to the Confederacy.

The Legacy of Cinco de Mayo

In the United States, Cinco de Mayo was first celebrated in California, thanks to its large population of Mexican immigrants. Most were vehemently opposed to the French occupation, and from 1863-67, the holiday served as a rallying cry for Mexican independence.

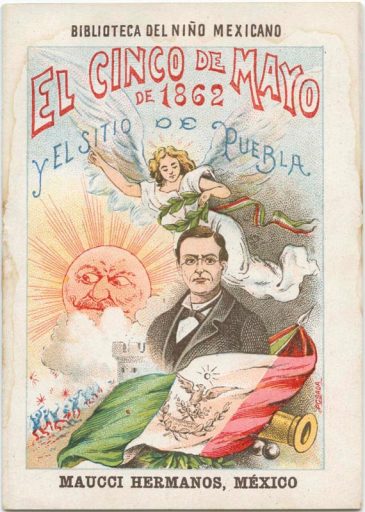

Cinco de Mayo poster from 1901 | Photo: Southern Methodist University

It wasn’t until the middle of the 20th century, though, that it began to enjoy widespread celebration in the US. During the rise of the Chicano Movement, which saw Mexican Americans fighting for economic, social, and civil rights from the 1940s to the 1970s, it gained popularity as a celebration of Mexican culture.

By the 1980s, it was observed throughout the country, and marketers had discovered its capacity to boost beer and tequila sales. Its popularity peaked in the 1990s, and while it’s still celebrated today, attendance at many major Cinco de Mayo events in the US has dropped significantly. It’s unclear exactly why, but we’d venture to guess it has something to do with the, uh, questionable tradition of thousands of white people getting hammered on Margaritas and stumbling around wearing sombreros.

Nevertheless, for a holiday that’s barely even celebrated in Mexico, Cinco de Mayo is doing pretty well. Presidents Bush and Obama both attended events, with the latter hosting several at the White House, and as of 2006 there were more than 150 official celebrations throughout the United States.

From 19th-century battle to modern drinking holiday, Cinco de Mayo has a storied past. So when you’re knocking back reposado and dancing to mariachi music this year, make sure you do it justice.