Recently, a new Panamanian rum aged for 18 years appeared on the scene, drawing howls of protest on the Ministry of Rum Facebook forum. The reason was two little words on the label: “Navy Rum.”

To rum purists, this is akin to saying Guy Fieri promotes haute cuisine. The issue of the Panamanian bottle isn’t the quality of the rum; rather, it doesn’t fit any of the criteria associated with navy rum. If you’re momentarily experiencing panic, not knowing exactly what navy-style means, that’s okay. There is no official definition, and it’s unfortunately not taught in schools. But that doesn’t mean you can dub any old rum as navy rum and expect folks to go along with it.

So what is navy rum, beyond a tankard of spirit consumed by sailors? Previously, I explained that hundreds of years ago, the Caribbean and parts of South America served as agricultural farmlands of the great European powers—in particular, France, Spain, and England. All had colonies making rum and navies transporting said rum back to the motherland.

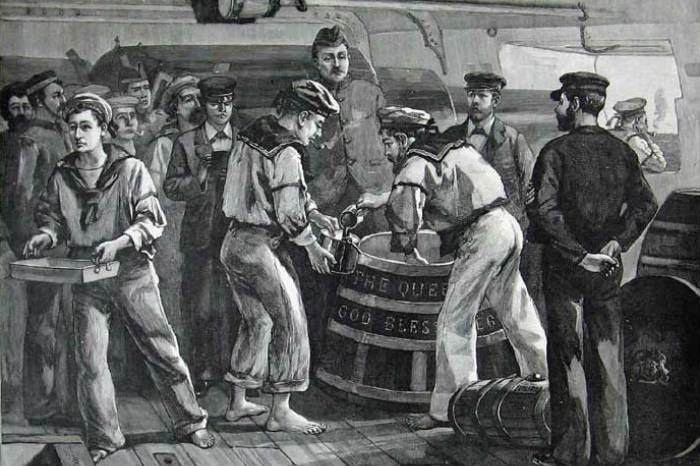

A confluence of factors made rum especially important to the British Royal Navy. Not least was the issuance of daily rum rations to sailors, a tradition dating back to at least the early-1700s. As navy ships travelled from port to port, they restocked their holds with many different provisions, including locally-made rums. The first major British colony was Barbados, followed shortly by Jamaica, and then Trinidad and Guyana. The common denominator? All are famous for making rum.

Early on, each naval ship had its own blend of rum, sourced from its most recent port visits. Eventually, there was a need to consistently supply rum for all British navy ships, not just those patrolling Caribbean waters. In 1784, the British navy contracted with James Man to supply rum, a task he and his company (now known as ED&F Man) performed until the navy’s daily rum ration was discontinued in 1970. Rum from the aforementioned colonies arrived at the London docks, where Man aged and blended them to create a consistent product.

You could then say that Navy rum is a specific recipe, that made by ED&F Man. However, they stopped making it in 1970, yet there’s still plenty of “navy rum” being sold today. (As an aside, some of that ED&F Man blended rum can still be bought. Pick up a bottle of the Black Tot Last Consignment. It’ll run you $1,000 or more, but you’ll taste history.)

Rum experts usually agree that navy rum is a blend of aged rums from two or more of the following colonies: Barbados, Jamaica, Guyana, and Trinidad. Some add that it should include rum from the Port Mourant double-wooden pot still in Guyana, known for its earthy flavor profile. Furthermore, some say navy rum should have a certain alcohol content, which brings us to the next term: navy strength.

What Is Navy Strength?

Black Tot Rum is made from the last stocks of the British Royal Navy’s rum supply.

Completely orthogonal to where a rum is made is its alcohol-by-volume, or ABV. Rum in the ship’s holds might inadvertently spill on the all-important gunpowder, so the navy required rums to be of sufficient ABV that rum-soaked gunpowder would still ignite. A popularly cited (if slightly misinformed) value is 57.15 percent ABV, or 114.3 U.S. proof; it may not be coincidental that this is almost exactly the fraction 4/7—making for easier shipboard math. In reality, navy strength is 54.5 percent, or 109 U.S. proof, which the British navy established after a thorough study. In general practice, 57.15% ABV still qualifies as navy strength.

A quick survey of rums with nautical sounding names shows there’s a fair number at 57 percent ABV, including the bellwether Smith & Cross. But don’t assume that the navy strength term only applies to rum. Navy strength gins are also quite popular.

Your key takeaway: Navy style is not navy strength.

Where Are the Navy Rums?

Pusser’s Rum lineup.

With our newly expanded background, let’s asses the navy-ness of a few popular rums.

The Pusser’s brand is an obvious starting point. Pusser’s bought the recipe from the British navy and claims to use it to make faithful replicas. However, observant folks have noted that the countries listed in the blend have changed over time. Recently, the entry level Pusser’s Blue Label became an all-Guyana blend, and the bottle now says it’s “inspired by” the original recipe. Either way, as a single-country rum, it doesn’t fit the navy rum definition. That said, their Gunpowder Proof (Black Label) stakes a claim to historical accuracy by being a blend of rums from Guyana, Trinidad, and Barbados, and it’s bottled at 54.5 percent ABV. It’s also quite good in a Navy Grog cocktail.

Smith & Cross is beloved by Jamaican funk aficionados. It’s bottled at 57 percent ABV, and the label accurately states navy strength. However, it doesn’t qualify as navy style, since it’s not a multi-country blend.

Velier recently released its Royal Navy Very Old Rum, a blend of very long-aged distillates from Trinidad, Guyana, and Jamaica that clocks in at 57.18 percent ABV. Thus, it’s both a navy style and navy strength rum. At 130 Euros or more per bottle, it’s a bit pricey, but quite delicious.

Plantation Rum O.F.T.D. Overproof hits the right navy style notes—a rum blend from Barbados, Guyana, and Jamaica. However, at 69 percent ABV, it’s well beyond navy strength. A proper description instead is “navy style overproof.”

According to their site, Lamb’s Navy Rum has rums from Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad, and Guyana, so qualifies as a navy style rum. Yet it’s available at both 40 percent ABV and 75.5 percent ABV—neither of which is navy strength.

As for the 18-year-old Panamanian rum, well… it’s now clear why the navy rum aficionados gave it a good mocking. Not only is it bottled at 40 percent ABV and comprised of rum from just one country, Panama was never a British colony. It’s highly unlikely that a Panama-made rum ended up in British sailors’ daily rations.

Are rum purists taking all the fun out of rum by insisting on fidelity to historical truth? I contend not. Rum’s reputation as a world class spirit has suffered for decades because of an “anything goes” approach to marketing. If rum wants to be perceived in the same realm as single malt scotch or bourbon, its proponents need to understand and convey its traditions accurately.

Matt since you are from Seattle, you should check out the Puget Sound Rum Co in Woodinville. They have an experimental release of Navy Strength Rum which is 57% abv. It was delicious!

Matt, Thank you for your knowledge and expertise about spirits and especially Rum. I am a new rum afficonado. During my early bartending years my familiarity to rum was limited to at best Bacardi and Coke at the local watering hole. I didn’t care for the taste at all. About 10 years ago, on a particularly hot day, on a whim, I purchased an inexpensive bottle of dark rum and some pineapple and orange juice to mix and fell in love. I’ve since had the pleasure of trying many delicious rums and blends and love to mix them with mixed fresh squeezed juices, orange, lime, pinapple. I’ve since had the pleasure of converting many people into the ranks of Rum lovers. We take turns buying and trying Rums that we read and hear about that we individually can’t always afford. I’m looking forward to trying some of the rums that youve mentioned here. Surely nothing could be better than liquor made out of wonderful, sticky, sweet molasses. If the Navy still gave out a daily ration, I’d enlist!

Splice the Manbrace Hearties!

Keep in mind that the “proof test” established the minimal strength for rum, not the absolute standard. Higher proof rums were certainly stored in barrels aboard naval vessels since they purchased barrel proof product. The old field test represents the lower range of acceptability. Efforts to define Navy Rum can only be expressed by the Navy, not rum pundits.

Yes, what Paul says below. The rum ration predates the ability to accurately measure the strength with hydrometer, so the gun powder test was used to demonstrate the spirit was at strength and not diluted. They also stored casks of water, beer, and wine so if they can’t keep their precious rum barrels from leaking they might not store the liquids next to the gun powder…

The Royal Navy proof rum ABV has nothing to do with spilling onto gunpowder. In fact it’s almost the reverse. Sailors did not wish to be diddled on their ships purchase of rum so to ensure it was quality a cone of gunpowder drizzled with rum was ignited. If the powder flashed then the rum had not been watered down which proved it’s strength ( or as we now day proof)

Trust me I’m ex Royal Navy.

Hi Paul – It’s true what you say about sailors not wishing to be cheated on their rum rations. That’s a topic I didn’t wish to get into on this short piece. However, that doesn’t necessarily contradict the part about ensuring gunpowder is still viable.

I can’t turn up an original source that explains why the British Navy established 54.5%. The best I can find is Simon Difford’s writeup, which says that gunpowder proof was useful for both reasons, as stated here: https://www.diffordsguide.com/encyclopedia/192/bws/navy-strength

It’s both – shipboard storage was at a premium, so storing rum that would not affect the gunpowder if it spilled was space-efficient when stored in proximity.