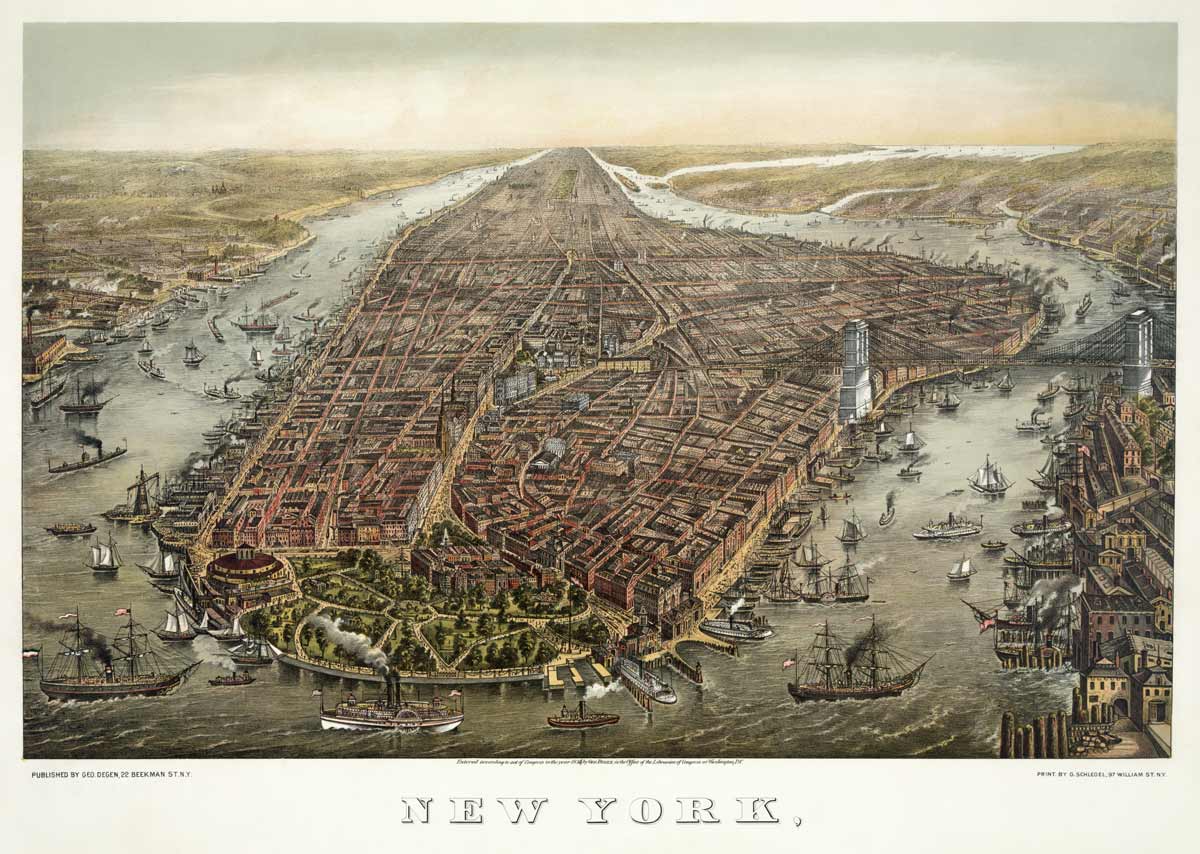

This is part one in a four-part series by New York Cocktails author Amanda Schuster about New York’s role in shaping how we drink. Read parts two and three.

There is much talk about the influence New York City culture has on the modern cocktail movement. However, it’s amazing how many misconceptions there are about when, exactly, it began—as though using fresh sour mix and esoteric liqueurs in drinks is something that only started happening in the past couple decades.

The reality is that there have always been bars in the Big Apple as well as celebrity bartenders. However, compared to today, very little of their work was recorded and properly attributed. For the most part, it wasn’t until the self-described cocktail geeks in the late 20th century started comparing notes and collecting their books (the first editions of which are now worth a small fortune) that people started paying attention to them again.

What is more recent is the “pictures or it didn’t happen” trend of sharing recipes on visual platforms like Instagram. And sadly, before the modern era, only the people who really sought out the spotlight were credited for their drinks and techniques. There were probably hundreds of barkeeps around the city who served impressive cocktails at taverns and saloons, but a century later, we only have records of a few. Still, we can be thankful to those who wrote down their findings.

Below, we detail some of New York’s most famous pre-Prohibition bartenders, and how they impacted modern cocktail culture.

Jerry Thomas

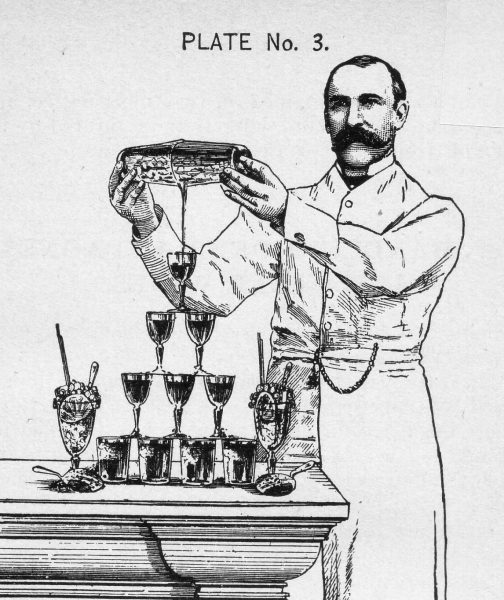

Professor Jerry Thomas mixing a Blue Blazer cocktail

Professor Jerry Thomas’ bar, located in what is now referred to as the Flatiron neighborhood, became famous for the inventive drinks he served there. At the time, changing up a single ingredient in a drink, or employing a vessel with a non-traditional shape, was interpreted as mind-blowingly progressive and new. And this guy went all out. He learned to throw flaming drinks between mugs to make the Blue Blazer and other techniques while traveling the world, all for the sake of impressing guests.

His 1862 book Bartenders’ Guide (How to Mix Drinks, or the Bon-Vivant’s Companion) is a landmark publication geared toward the profession of mixing drinks that, until then, had never existed in such a capacity. It is here that some of the world’s most famous drink recipes (such as the Improved Cocktail) and techniques were first published, and it continues to be an indispensable reference to so many people interested in drinks culture.

Dale DeGroff, who is referred to as “King Cocktail” and considered one of the founding contributors to the modern cocktail movement, would have been up the mixing tin without a jigger if it weren’t for Professor Thomas’ legacy. In the early ‘80s, restaurateur Joe Baum employed young DeGroff as the head bartender in the second revamping of the Rainbow Room, with what was then considered a revolutionary concept: classic cocktails with fresh ingredients. Baum shoved a copy of the Bartenders’ Guide at DeGroff and basically said, “Here, kid. Figure it out.” The rest is history.

William “The Only William” Schmidt

Photo from diedurstigeseele.de

For about 16 years “The Only William” was the most famous bartender in the world, helped along by an article written in the The New York Sun about the fanciful drinks he served at The Bridge Saloon at the base of the Brooklyn Bridge. Born in Hamburg, Germany, he immigrated to Chicago in the late 1860s and already had a following by the time he moved to NYC in 1884. Recipes from this “acrobatic” bartender can be found in the 1892 book The Flowing Bowl: When and What To Drink (the first edition, along with Bartenders’ Guide, can be viewed for free on euvslibrary.com).

Compared to Thomas, they seem a bit fussy now, and the book contains many complicated, multi-ingredient recipes with products like crème de roses. However, the book also lends some interesting insight into technique, history, and ingredients in the opening pages—information intended to maximize bar service potential. He is known for having created a $5 recipe at a time when drinks cost only 15 cents, although according to cocktail historians like Jared Brown, Anistatia Miller, and David Wondrich who have searched high and low for it in newspaper archives, the recipe is lost. In fact, many of his drink recipes were never recorded because he was known for his showmanship, often creating new mixtures on the spot.

In a way, the modern movement toward drinks with several layers of flavors and all manner of tinctures and exotic liqueurs can be traced back to Schmidt. However, he’s also famous for his simple punches meant to serve a crowd, and for creating the refreshing cognac sour cocktail, Alabazam, which can be interpreted as a less sweet, tall variation of the Sidecar.

Harry Johnson

Another successful German-born bartender was Harry Johnson, who got his start at hotels and steakhouses like Delmonico’s. He amassed such a following at a certain point, with distinguished guests like Boss Tweed and Ulysses S. Grant, that he was able to open his own bars around the city. If we had a time machine, it must come equipped with a setting to visit Johnson’s swank, ornately furnished Little Jumbo, a lounge located at 119 Bowery (now a wholesale furniture store). The bar’s sign was a list of drink names cleverly arranged in a pyramid shape, with Gin Rickey, from the 1882 edition of his Bartenders Manual, propping the upper tier. Rickeys, incidentally, are the fraternal highball twin to the Collins, with lime instead of lemon juice.

One of Johnson’s last gigs was in the early 1900s at Keen’s Chop House (back when it was still spelled with an apostrophe). The bar there, according to Jared Brown and Anistatia Miller in their fascinating peek into the era, The Deans of Drink, was what he considered the “perfect work station.” It is largely unchanged from that time, and is one of the quintessential spots in the city to sip a classic cocktail like a Manhattan or Martini amongst the great ghosts of bartenders past.

Honorable Mentions

Orsamus Willard: If you found yourself at the City Hotel in 1815, the signature drink was his Apple Toddy, which Jerry Thomas tweaked for his book decades later.

Martha King Niblo and William Niblo: Back in the 1830s when SoHo was a garden district, the backyard of this establishment owned by this couple is where all the art and theater people convened, and drank the earliest known versions of Sherry Cobblers.

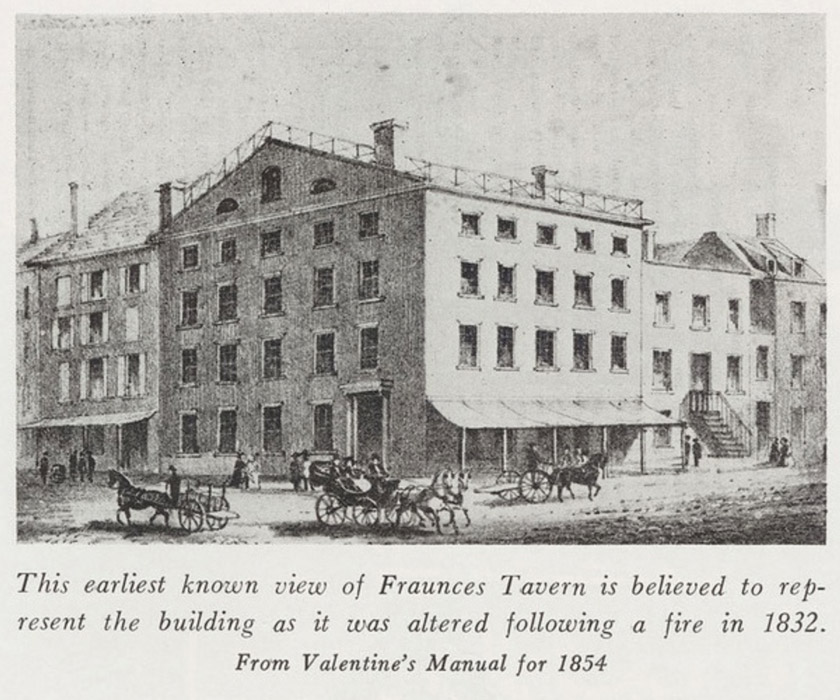

Anyone who worked at Fraunces Tavern in the mid to late 1700s: This establishment, having survived numerous fires and revolutions, still stands in Lower Manhattan next to The Dead Rabbit.

Photo from the Fraunces Tavern Museum

It’s where the Sons of Liberty met over numerous drinks as they hashed out plans to start a whole new independent country, and where George Washington bid farewell to his troops in 1783.

Can you imagine the pressure? What might have happened if service had gone wrong? If someone gave them a negative Yelp review and the bar was forced to close? Sadly, we don’t know the names of the people who worked those nights. But their souls deserve a good tip.

A 19th-Century Cocktail Blueprint

We owe a debt of gratitude to these pioneering New York bartenders for shaping the way mixed drinks are presented in the modern era. Sure, we don’t measure in “ponies” anymore and some of the ingredients are lost to time, but their 19th century recipes and techniques serve as a fascinating, useful blueprint for modern cocktail making.

If you really want to learn how it’s done, get off the internet and pick up a book or dig into some newspapers archives. There’s a wealth of information to be served up about our nation’s cocktailing past that still can’t be found online.

Editor’s note: This post was updated on October 17.