This is part three in a four-part series by New York Cocktails author Amanda Schuster about New York’s role in shaping how we drink. Read parts one and two.

The “end of an era” is a phrase we’ve heard a lot in New York City these past few weeks as the Flatiron Lounge closed its doors on December 23. Co-founded by industry pioneer Julie Reiner with other partners in 2003, it was the first cocktail bar accessible to regular New Yorkers, i.e. ones that couldn’t be bothered fumbling for a number, finding a hidden entry, or being subjected to other obstacles just to get a drink. It was elegant without being ostentatious. The drinks were upscale without being too esoteric.

A non-industry friend told me it opened around the same time she moved to the city from Detroit, and it made her feel “chic, grown up and cool.” She told me: “Flatiron Lounge helped me fake it ‘til I made it.” It had a sign, an address, a phone number. It also had exceptional drinks prepared by a revolving roster of bartenders who would go on to cocktail stardom throughout the city. It opened at a time when finding a well prepared cocktail with fresh ingredients was still a challenge, but things were about to change.

If New Yorkers who weren’t already self-styled cocktail nerds were drawn to this type of venue, then it was clear a revolution had taken place. Decades before, the City That Never Sleeps was also one that never juiced a lemon. In a previous article, I told the story of how Dale DeGroff, a.k.a. “King Cocktail”, was charged with overhauling the menu at the Rainbow Room with a copy of Jerry Thomas’ Bartenders Guide tucked under his arm. He wasn’t the only bartender making these kinds of drinks, but there certainly weren’t many in the 1980s, when NYC was still very much in a Rum ‘n Tab, powdered sour mix rut. Those who knew better would discover a bartender they liked, usually tending bar in a hotel or little den somewhere with no fanfare, and make a point of visiting that person for a proper drink. This one makes a good Martini. That one buys fresh limes for Daiquiris. This one keeps a bottle of bitters handy for a Manhattan…

Forming the NYC “Cocktail Yankees”

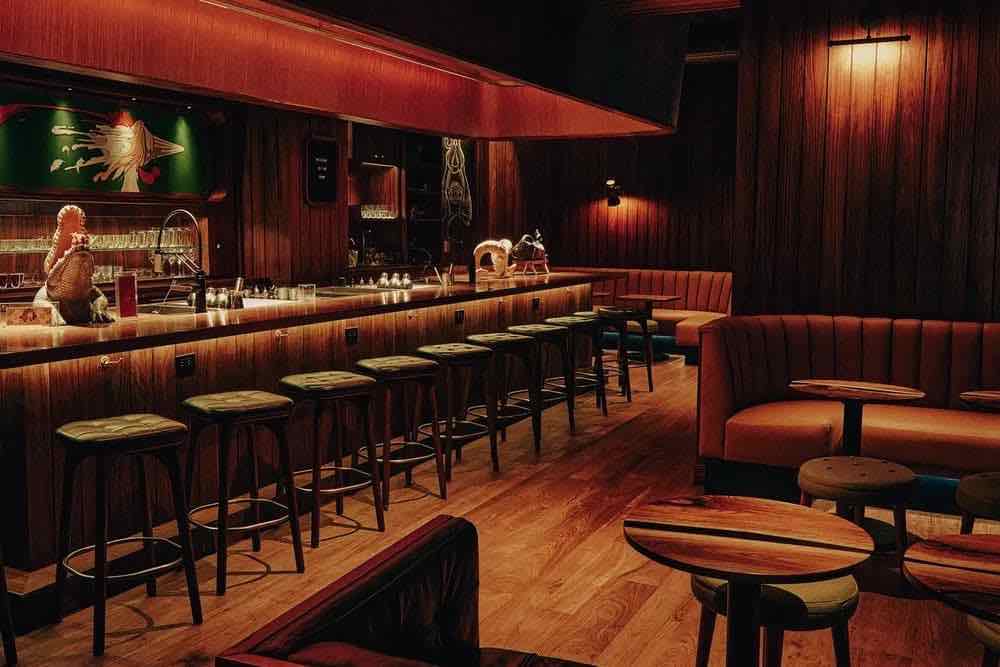

Opened in 2004, Employees Only was a pioneer of NYC’s cocktail renaissance. Photo: Emilie Baltz.

A Proper Drink, incidentally, is the book by Robert Simonson detailing the movement that followed. It should come with a flow chart. This person worked here with this person, who went on to open this bar, who trained this person, who opened a bar with these people, etc. For instance, eventually, DeGroff gained enough experience that he could mentor other bartenders and move on to other venues like Blackbird and Bemelmans, where he worked with Audrey Saunders, who opened Pegu Club in 2005.

At the time, finding a staff for a craft cocktail bar making its own house ginger beer for drinks like the Gin-Gin Mule was challenging because working behind the stick there required a skill set most bartenders simply didn’t have. That elegantly appointed room, (still one of the only places in the city to find a hot Tom & Jerry when the temperatures plunge), saw a roster of bartenders that included Phil Ward, Toby Maloney, Chad Solomon, St. John Frizell, Jim Meehan, and many others before the next cocktail wave dotted the downtown scene with Employees Only, Death and Co., Mayahuel and PDT.

For my book New York Cocktails, I spoke to Joaquín Simó, who worked at Death & Co. before opening his own place, Pouring Ribbons, in 2012. He explained there was a dream team of bartenders working around the city—”the cocktail Yankees,” some people called them (clearly not Mets fans). Before the age of social media and smartphones, bartenders like Simó would keep written lists of where people could be found and when—Sasha Petraske at Milk & Honey, Jim Kearns at Death & Co., and so on. He’d visit on his off time from building up the menu at a little restaurant bar. Places around town were quietly shifting into the fresh ingredient era and stocking better quality spirits.

The speakeasy style still had its draws, though. Even before Flatiron Lounge, Pegu Club and the rest, there was Angel’s Share, opened in the mid-1990s. Located inside a Japanese restaurant, it’s accessed through a hidden entrance that takes a certain degree of geographical mastery to find. The service there is impeccable, the drinks creative and exquisitely presented, and from its inception, the bar—which also stocks one of the best whiskey collections in the city and was one of the first to make high quality ice—has been packed despite its challenging entrance. One of its biggest fans was Sasha Petraske, who transposed many of those fine drink-making and serving details for Milk & Honey, and subsequently Little Branch, Middle Branch and all of its siblings around the world.

Petraske, who tragically passed away suddenly in 2015, was a stickler for certain levels of service and presentation. Lucinda Sterling, who now manages Middle Branch, explains that it’s simple but priceless service details that make it work, such as ensuring that every guest in a party receives their drinks at the same time. Why? So they can toast together, of course.

Drinking Like It’s 1959

Don Draper has a drink. Photo: Mad Men / AMC.

It helped that retro TV series like Mad Men, set in the 1950s and ’60s, had become popular. Suddenly, everyone wanted to visit a swanky bar and drink Old-Fashioneds and Martinis like Don Draper or Peggy Olson. Stylish venues such as Raines Law Room popped up. The name is in reference to a 19th century liquor law that prohibited the sale of alcohol on Sunday except in hotels. Saloons easily worked around it by creating bedroom-like settings where there were none, therefore Raines Law Room is set up in a series of dreamy, plush vignettes with a call button for service. Meaghan Dorman became its head bartender and made the place so successful, that she was able to open the equally dreamy Dear Irving in 2014, which is decked out in a series of rooms each evoking a different era in time from the ’70s back into the 19th century. The theme has been so popular that Dear Irving now has a luxe second location, this time high up in the Aliz Hotel in Times Square, which opened in mid January.

Cocktail bars weren’t relegated to the main island anymore, beginning to crop up all over Brooklyn and Queens, and even spreading into neighborhoods with less foot traffic. They were even becoming so specific that they focused on a single spirit or category—tequila bars, rum bars, and, of course, Amaro y Amargo with its focus on bitters.

You Can Try This at Home

The Aviation Cocktail. Photo: Erich Wagner / Wikimedia Commons

However, people still wanted to make cocktails at home when they could, and it was up to a good liquor store to stock the goods, especially when importers like Eric Seed, founder of Haus Alpenz, was beginning to bring back ingredients like Creme de Violette and Velvet Falernum. These liqueurs were lost to Prohibition or dropped from importer priority stock, but suddenly necessary again as cocktail geeks wanted to make an authentic Aviation or throw a tiki party.

I first met Eric when I was the assistant spirits buyer at Astor Wines and Spirits around 2006/2007. We became fast friends, and I would accompany him on cocktail adventures around town. One Halloween, we entered a cab and he instructed the driver to take us to Red Hook. I panicked. Not because I was afraid of the neighborhood, but I guessed where we were headed. As soon as I entered the home of LeNell Smothers (now LeNell Camacho Santa Ana), owner of LeNell’s Boutique, the city’s premier destination esoteric spirits store, I knew I was toast.

“Eric, don’t you understand that woman despises me? I’m her competition. She’s never forgiven me for stocking your Batavia Arak before she could.” Boy was I right. She didn’t kick me out, but she pointed and shook her head, refusing to serve me a drink. I would never have guessed back then that once the dust settled across the city and St. Germain was considered old hat, and I’d moved on from the retail game, that we’d become lifelong friends (she has since re-opened LeNell’s in Birmingham, Alabama), chatting up Toby Cecchini together at Long Island Bar about the good old days of his classic, now long shuttered joint, Passerby, while he avoided our order for Cosmopolitans. It certainly took some winning her over, just as it did to get the inventor of the drink (at the Odeon in the 1980s) to finally serve us one at the end of the night, like playing a greatest hit as a concert encore.

“Won over” is precisely how to describe the cocktail-related change that had taken place all over town—even in parts of Staten Island and beyond. Sadly, that sea change also comes at a cost. Now that there are cocktail bars everywhere, how do they keep the lights on? Clearly, $30,000 is way too much to ask for a space like Flatiron Lounge, as delightful and inviting as it always was. Things are shifting again in the city, so you’d better visit your favorite bars while you can.