This is part two in a four-part series by New York Cocktails author Amanda Schuster about New York’s role in shaping how we drink. Read parts one and three.

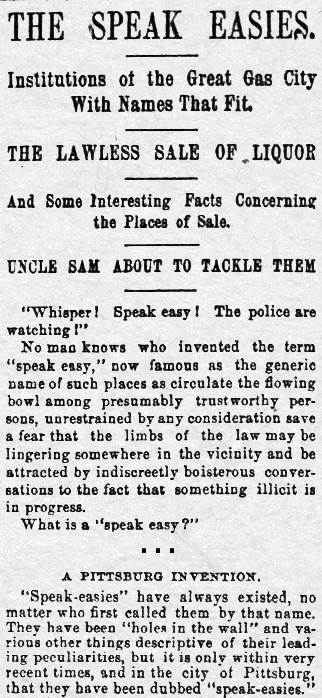

It all seems so romantic now—the unmarked entryways, the secret passwords, the trick doors, an unaged spirit made in secret by the light of the moon. Since the Volstead Act prohibiting the production, sale, and transport of “intoxicating liquors” was repealed in 1933, American liquor laws seem downright puritanical in comparison to the days when it was supposedly illegal to drink without a prescription or religious dispensation.

When Prohibition was proposed, it was a widely held belief that port cities with strong immigrant populations were the primary targets of the anti-drinking movement because this is where the grand, polished saloons and pubs the prohibitionists hated most thrived. The notion of the “roaring twenties” was popularized decades later, especially referring to those years in New York City, for the very locations the law was meant to discipline were the ones that best got around it. However, while the city was home to swank speakeasies and all-night parties, these came at an extreme cost to health and safety.

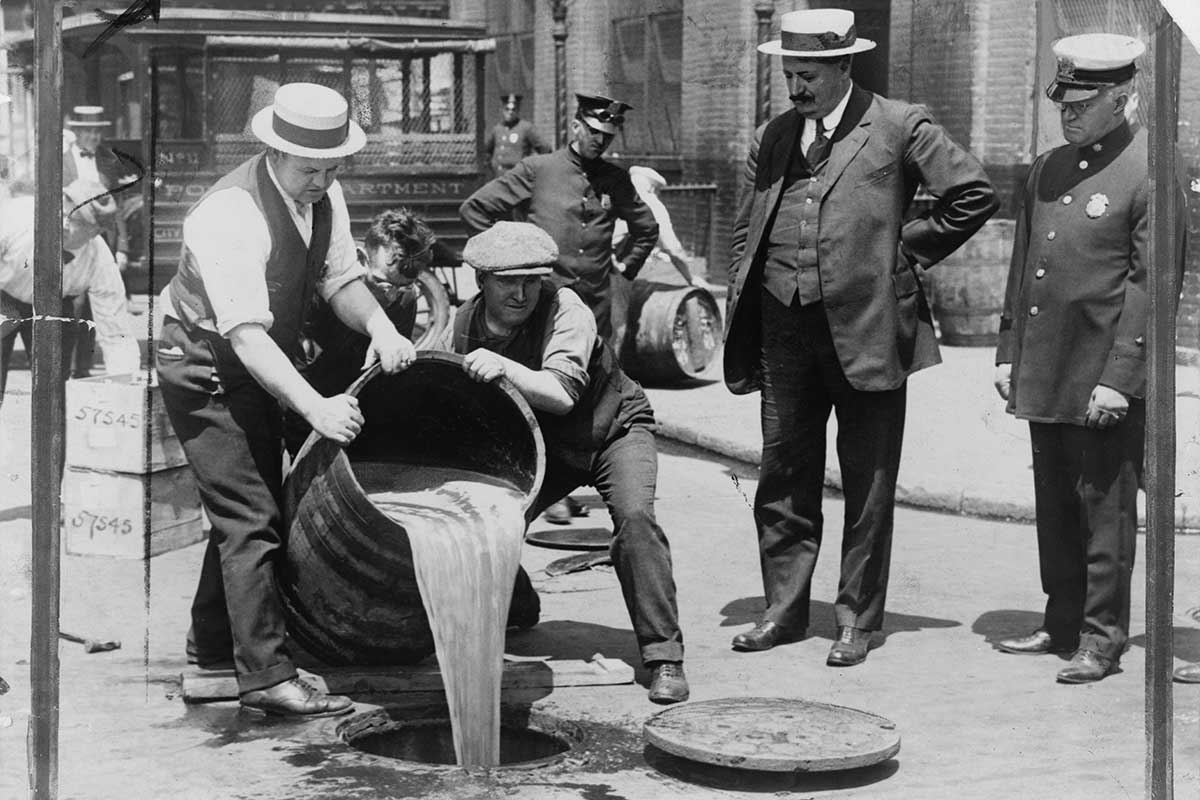

Prohibition Disposal in NYC

One of my favorite bars of the early 2000s in Brooklyn was the now-defunct Jakewalk, which was a horrible name for a bar. It glamorized a condition known as “jake walk”—a tragic, severe, and incurable neurological disorder affecting the hands and feet that led to an unusual gait. It was caused by drinking the tri-o-tolyl phosphate (TOCP) in Jamaica ginger that was passed as a cheap substitute for drinkable alcohol at the time. Bathtub gin was dangerous, too, and that’s before you even factor in the police raids and mob shoot-outs.

There is a very good reason why some of the city’s best bartenders like Harry Craddock scrammed for foreign shores to the civilized bar cultures of London, Havana, or Paris (the latter sought out for its higher tolerance of different races and sexual preferences, and welcomed women who thrived as artists and business owners) before the first month of the so-called “Noble Experiment” even passed.

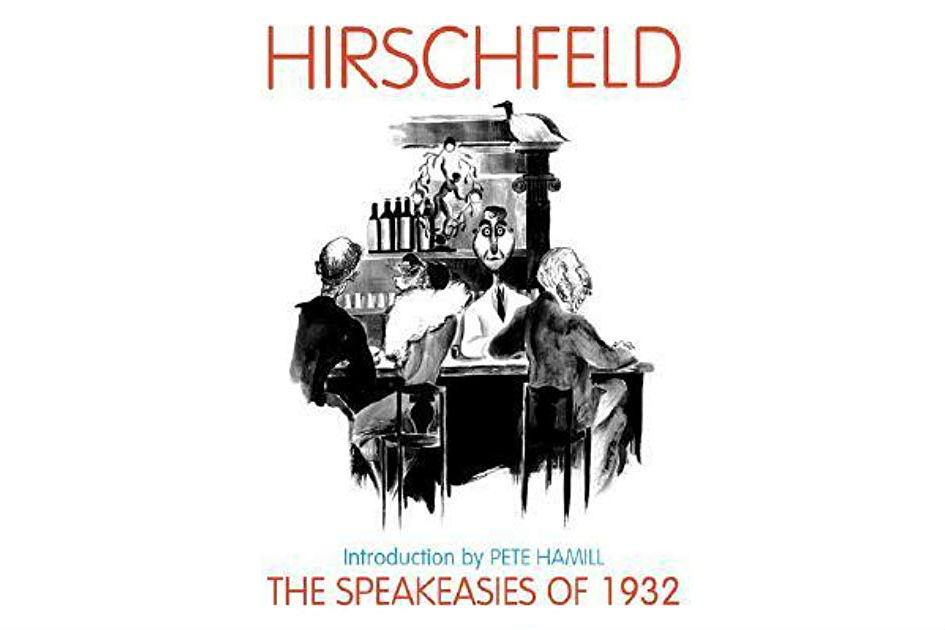

The Speakeasies of 1932

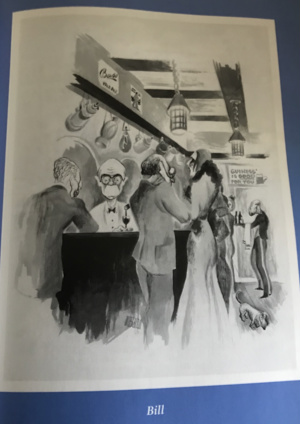

Photo: Applause Books

However, bar culture wasn’t dead, just different and not as dependably lucrative. What is inarguably the best document of Prohibition-era New York City was written in the last year of it—The Speakeasies of 1932 by caricaturist Al Hirschfeld. It practically functions as an instruction manual to illegal drinking in the Big Apple, with reviews of the best hidden (some in plain sight) bars around town, as well as what booze they stocked, the best cocktail to order, best times to go, whether women were allowed, best discussion topics to engage in with other regulars, whether the establishment served free food or lunch, etc., and personality profiles of the head bartenders. The exact location of each venue was provided (sadly, about 85 percent of them are no longer operating as a bar or restaurant), with directions on how to access them.

The night of January 16, 1920, when Prohibition went into effect, was said to be one of the most bitterly cold, bleak and inhospitable in the city’s history. However, by 1932, what turned out to be the last year of anti-drinking law, the city was well thawed out. New Yorkers had adjusted to it so comfortably, and where to get a drink was such common knowledge, Hirschfeld publishing such a book no longer seemed verboten. For instance, at one of the speakeasies, the Press Grill at 152 E. 42st St., he writes: “such over-elaborate pains are taken to conceal the fact that it’s a speakeasy, that it shrieks out there’s whiskey to be had within. Entrance is directly from the street to a blind dining room to the bar…”

Firefly4342 [CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikipedia]

On the other end of the spectrum is the Mansion at 27 W. 51st St., an upstairs affair in a fine townhouse that is “…a former banker’s idea of the Lycée Palace.” Hirschfeld goes on to describe a “breathtakingly spacious entrance hall” and “circular, spacious and exquisitely decorated” barroom hosting “the cream of municipal bureaucracy” and “drinks begin at a dollar. One of Prohibition’s greatest blessings.” The profile ends with a recipe for a Brandy Crusta:

“Moisten rim of small wineglass with lemon, dip rim in powdered sugar to give glass frosted appearance, peel rind of ½ lemon and put in bottom of glass, then pour into shaker one teaspoonful of sugar or grenadine, three dashes of maraschino, three dashes of Angostura bitters, juice of ½ lemon, one glass brandy. Shake well, pour into glass, and add fruit.”

Surviving Stalwarts

Of the Prohibition-era bars still in existence today, one of the most famous is the Stonewall (later called the “Stonewall Inn”) at 91 Seventh Avenue. Hirschfeld describes an entrance that is “so uniquely bold that knowing that it’s an alcoholic haven is the open sesame.” Of course, decades later in the 1960s, this would be the scene of the Stonewall riots and the launch of the pride movement in New York. Little could Hirschfeld have known in 1932 sitting with an illicit dram of rye in front of Bill the bartender, “a funny old gentleman with a caustic tongue and lash-like sense of humor,” that this bar “strewn with rough-hewn logs” would become national landmark in 2015.

Jack and Charlie’s, the Speakeasies of 1932.

One of the most well appointed speakeasies profiled in the book is what Hirschfeld refers to as “Jack and Charlie’s” at 21 W. 52nd St.—”an example of what decorative restraint, spaciousness, excellent cuisine, and nonpareil beverages will do for a place… the only place where you can call for Dewar’s, Teacher’s, Walker’s Black Label, or any other brand of whiskey and get just that.”

The joint he is describing is what is known in the modern era as the famous celebrity haunt, the ‘21’ Club, which was opened by cousins Jack Kriendler and Charlie Berns on New Year’s Eve, 1929. That’s right, they opened a bar as a viable business during Prohibition. The original bar area, now in its main dining space and moved across the room, was fitted with shelves which automatically collapsed at the push of a button, with a hidden chute that let the bottles crash underground if the feds showed up. (In the 1980s, when the Paley Center broke ground next door, it was said a strong stench of alcohol emanated from below.)

21 Club (via 21club.com)

Even with all that whiskey, ‘21’ is best known for its Southside gin cocktail, which was the house drink at the Puncheon, Jack and Charlie’s other bar on 49th St.

Southside Cocktail Recipe

2 oz gin

1 oz mint simple syrup (add several sprigs of mint while preparing standard 1:1 recipe and strain out)

4 to 5 fresh mint leaves

Juice of one lemon

Splash soda

Vigorously shake all ingredients with ice in order to work that mint. Strain into a Collins glass filled with fresh ice and garnish with fresh mint.

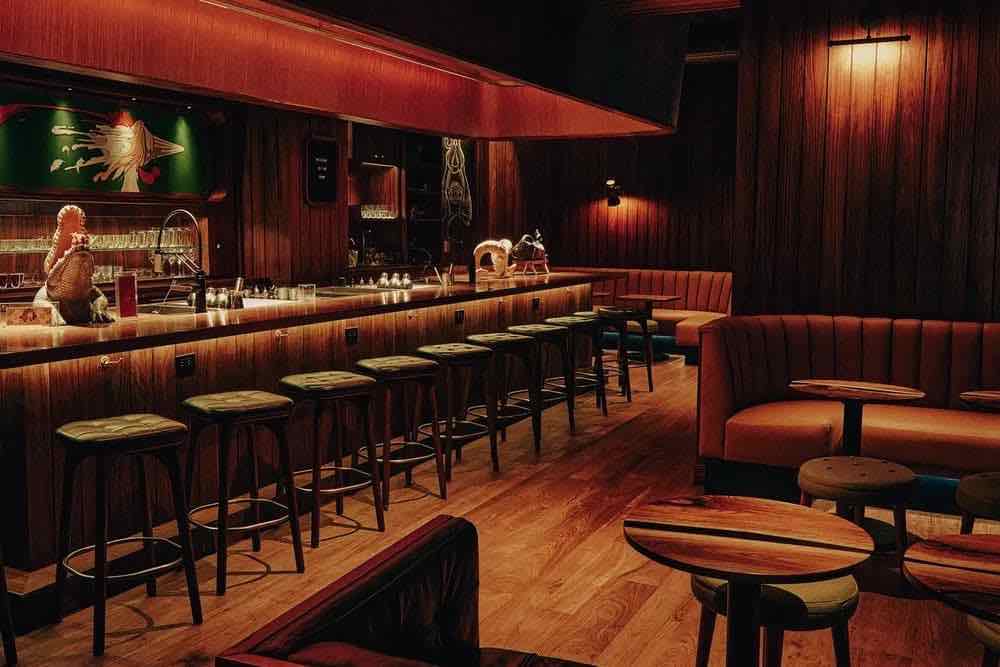

Then, of course, there is Chumley’s, at 86 Bedford Avenue (and yes, there is something to the theory that to “86”—kick someone out of a bar—comes from there), the iconic mid-19th century tavern purchased by Leland Chumley in 1922. The partial stable house with the back entrance off its courtyard and secret passageways made it an ideal speakeasy, with easy access for liquor deliveries and a multitude of escape routes. In the 1940s through the 1970s, it became known as a casual writer’s hang, although, as I say in my book New York Cocktails, its most recent renovation and takeover makes it so lavish, the only writer who can afford to patronize it these days is J.K. Rowling. Still, it’s worth a peek (if not a $30 Martini) to catch a glimpse of NYC history, even if it feels more like Chumleyland now.

The City That Never Sleeps was never quite the same after Repeal, for we are now required to take a nap between 4am and 8am. Only last year were we given permission to dance in bars again, but you still can’t buy beer in the same place that sells you liquor or wine (or fruit for your cocktail garnish, for that matter). At least you can buy alcohol, although it’s time we dispensed with the unmarked doors and gimmicky entrances—you don’t have a speakeasy, you have a bar with a difficult entrance; if you’re producing legitimately legal, unaged whiskey, it isn’t “moonshine.” We’re lucky to not need those things anymore. Let’s just have a drink.