Everyone knows that Ireland makes whiskey. Yet few know that its whiskey industry was nearly extinct in recent memory—and that what we think of “Irish whiskey” today is quite different from the historical mean.

One person working to change those perceptions is Donal O’Gallachoir, a co-founder of the Glendalough Distillery in County Wicklow, Ireland. O’Gallachoir, who is also Glendalough’s National Brand Manager for the U.S., served as my guide through the rise, fall, and rise of Irish whiskey.

The Water of Life

Like many spirits, the story of Irish whiskey begins with monks.

“Irish monks would travel through society, describing different techniques. They came across an early form of distillation, and they brought that back to Ireland and started to distill,” O’Gallachoir says.

Glendalough’s Black Porter-Aged Whiskey

These first distillations weren’t what we would think of as whiskey, but one of its unaged predecessors such as poitín, aqua vitae, or usquebaugh, a Gaelic word meaning “water of life.” Knowledge of distillation spread from the 6th century onward, but it remained a feature of agricultural life, used by farmers to turn excess grain into a tradable commodity. Then came the 16th century Tudor Conquest, which brought the English, and Anglicization, to Ireland.

“They got a taste for usquebaugh, and they Anglicized it,” O’Gallachoir says. “They used to call it usque, and then whiskey, and that’s really where everything changed.”

English imposition wasn’t limited to language. They began to tax whiskey, with predictable results.

“The Irish did what the Irish did, and they started to evade the taxes,” says O’Gallachoir.

More distilleries opened, reaching a high-water mark of around 2,000 (licensed and illicit) as distilling made the jump from being an exclusively rural affair to taking place in towns and cities, too.

“The Drink of Russian Czars”

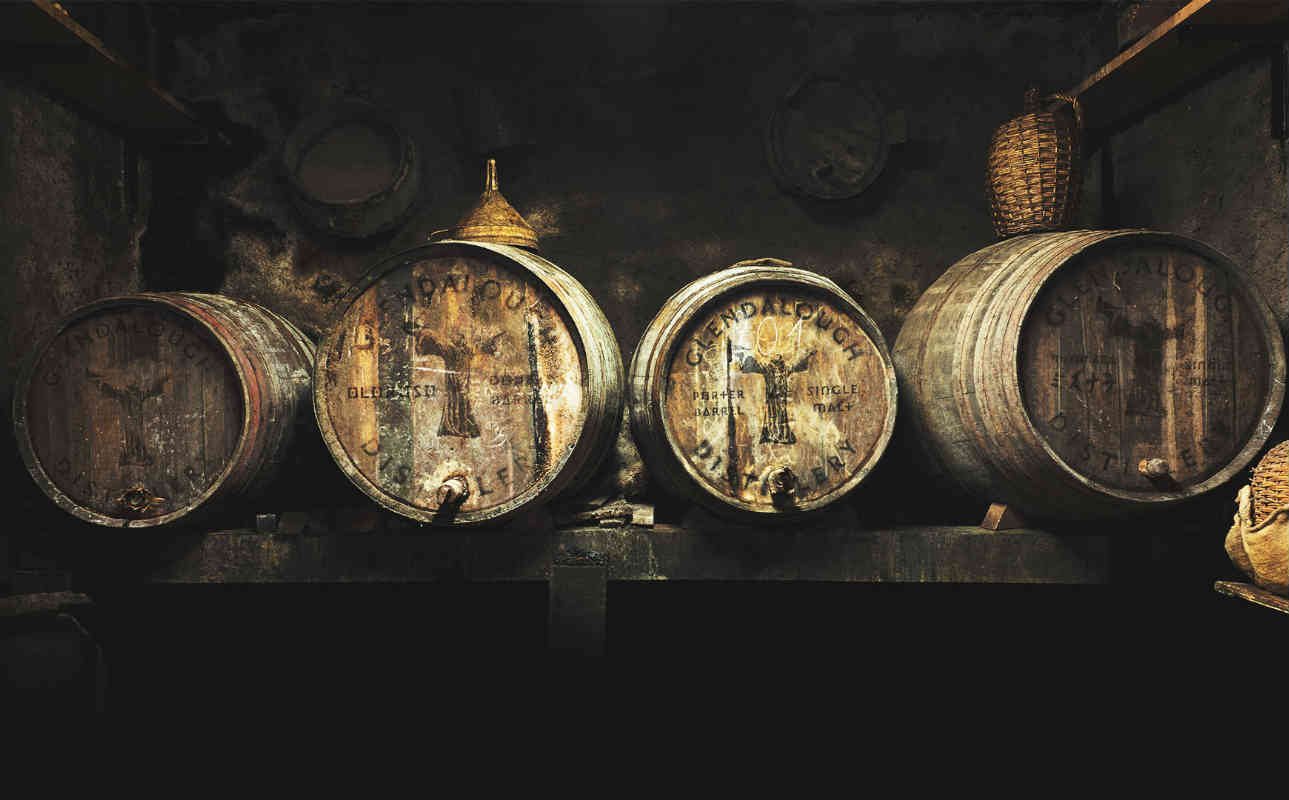

Glendalough Whiskey Barrels

In 1661, Charles II tried to crack down on the industry’s exponential growth by requiring an English grant for legal distillation. This move helped establish the bigger distillers, who further refined their distillation techniques and took advantage of the trade, bringing sherry, port, and madeira casks into Ireland.

“The 1600s, 1700s, and 1800s are where you start seeing whiskey aged in casks. And from that period onward, Irish whiskey becomes king,” O’Gallachoir says. “It is the drink of Russian czars, aristocrats, royalty, and it’s the dominant whiskey in the U.S. right up until prohibition.”

When the fall came, it was fast and steep.

“In a handful of years, Irish whiskey goes from 80-90 percent of the world’s whiskey consumption to non-existent,” he says.

The Dark Days

Glendalough Cocktail / Facebook

Five events in quick succession nearly ended Irish whiskey for good. The first blow was World War One (1914-1918), which proved ruinous for exports. The subsequent Irish War of Independence (1919-1921) and Irish Civil War (1921-1923) further impacted business.

The newly free state was soon embroiled in a trade war with Britain, which cut off not only the UK market but also the Commonwealth nations of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and India. But it was the United States that delivered the final blow.

“When it can’t get much worse for Irish whiskey, you guys introduce prohibition over here, and that was the last nail in the coffin,” O’Gallachoir says.

In the meantime, blended scotch had filled the Irish whiskey-shaped hole in the market. All over Ireland, distilleries were shutting down.

“In the ’20s, ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s, all these massive distilleries go out of business one after another,” says O’Gallachoir. “And it’s absolutely crazy. It’s amazing that the industry was essentially saved.”

Saving Irish Whiskey

Gelndalough’s Donal O’Gallachoir spreading the good word about Irish whiskey.

With the help of the Irish government, the last whiskey makers banded together in 1966 to form Irish Distillers. To stave off total collapse, they closed the distilleries that were not profitable and consolidated operations at the newly built Midleton Distillery in County Cork (today Midleton continues to produce Jameson, Redbreast, Greenspot, Powers, and more). The only other distillery left standing was Bushmills in Northern Ireland. From a historical high of 2,000, Ireland was down to two.

Irish whiskey had survived, but now it would need to adapt.

“The whiskey drinker’s flavor profile had changed. And this has a lot to do with the adoption of blended scotch, which was a lighter, sweeter style,” O’Gallachoir says. “Historically, Irish whiskey was big and bold and viscous, and would be a lot richer than what became known as Irish whiskey today. There wasn’t any blended Irish whiskey to speak of before that amalgamation.”

The Present and the Future

As Irish whisky entered its second millennium, some within the industry began eyeing the past.

“I would say the 2000s is when we really wanted to create something,” O’Gallachoir says. “[We] took a lot of inspiration from the resurgence in craft distilling in the U.S. To look at these world whiskeys and then knowing our own heritage and knowing that we were the first place where distillation occurred… we wanted to bring that back.”

In 2011 O’Gallachoir founded Glendalough alongside co-founders Kevin Keenan, Gary McLoughlin, Barry Gallagher, and Brian Fagan. Since that time, Glendalough has released a poitín, a series of gins, and four unblended whiskeys. Each of its whiskeys is bourbon barrel-aged, then cask-finished in the likes of Oloroso sherry barrels, Irish porter barrels, or Japanese mizunara puncheons.

“What we try to do is make remarkably different Irish whiskey, looking at historical styles like single grain and single malt, and bring it to new depths with different cask finishes to make different flavor profiles that resonate with the whiskey drinker of the day, but also have that heritage and that story to it,” O’Gallachoir says.

Glendalough whiskey still

Future releases will reach further into the category’s past and the frontiers of its future. 2019 will see the launch of a 17-year-old mizunara finish and two whiskeys—a 25-year-old and a pot still—finished in wicklow, a species of oak native to Ireland that hasn’t been used to age whiskey in 300 years.

O’Gallachoir estimates that there are 23 distilleries now operating in Ireland, with many more on the way. Irish whiskey is the fastest-growing category in the United States, and enjoys double-digit growth on a global scale. For O’Gallachoir, the next challenge is getting the word out on what Irish whiskey has been, and what it can be.

Always Be Educating

“A big part of the next couple of years is going to be educating. It’s going to be these educational events where consumers who are interested, whiskey drinkers who are interested and have overlooked Irish whiskey, we want to put our arm around them and say, ‘try these things, try the crazy stuff. This is not what you think Irish whiskey is, and this is why.’ That’s what’s happening over the next five, 10 years. We’re developing a category.”

Judging from the results thus far, O’Gallachoir is feeling upbeat.

“I’m meeting people out there, and they’re asking me questions like, ‘Is it pot stilled or column stilled, what is the age, what is the density of oak, what are the grains being used?’ People are interested in Irish whiskey. There is such a world outside of Irish whiskey than what their older brother or sister or maybe their father drank. And they’re geekin’ out about it.”